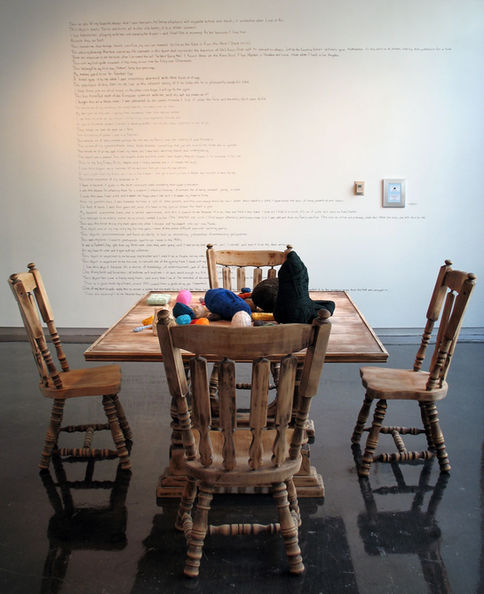

Conversation of the Others

table and chairs, donated objects, yarn, marker

2009

On the table lie close to sixty small objects, each delicately wrapped with various yarns in intricate linear patterns that hide their contents. Over the span of six months, I requested that people (some I knew, some I did not know) donate domestic objects for this piece. The “rules” for these objects were that they had to reside in your home, and they must be able to fit in your hand. The owner provided me with one sentence as to why it is important to them. Each object was then wrapped in its own individual color and texture of yarn; retaining the uniqueness and individuality associated with each donor. Through this bundling process, I am intentionally hiding the surface details of each object, enhancing the mass and weight of each item. The intricacy of the wrapping highlights the time and attention I spent with each object, transforming it into a piece of art with a protective “second skin.” They are presented as items that are specifically important to one person, but universally interesting to all. I stress the role that human habits or personal rituals play within a home by my careful, precise linear pattern wrapping, and I am instinctively protecting them, but also suffocating them. For some people, the home environment can be nurturing and comfortable, a place of solace, but for others, the home can seem stifling, overbearing, and a place of unrest.

The viewer is invited to sit and examine the objects: pick them up, move them, turn them over, and imagine what treasures these bundles may contain. The exchange of both visual and tactile information is similar to the feelings of anticipation and curiosity that are associated with giving or receiving a gift. These gracefully wrapped items indicate the preciousness of those small objects we display in our homes that reveal our individuality. Over time, these objects freely travel between artist and participant, generating a dialogue on ownership. At the table, the dialogue continues as viewers freely pass the objects around the table, constantly changing the spatial proximity of objects and thereby creating new compositions, object groups, and associations.

A list of the sentences identifying the significance of these objects is handwritten in on the gallery wall, adjacent to the table. No legend exists to identify which sentence belongs to which object. By keeping the specific object secret, I set up a game in which the viewer matches sentiment, emotion, and personal attachment with an object. This sparks communication with others that centers on the common compulsion to project our self-identity through possessions. More significantly, Conversation of the Others reminds viewers of our sentimental attachment to objects.

At the conclusion of the art piece showing, each item is returned to the donor in its wrapped state, once again becoming a gift. The donor is left with the ultimate decision to either accept the new art object and reintroduce it into their home environment, or to reclaim their original item by removing the yarn. This decision on the part of the donor raises many questions, one being: Which is more important, the visual aspects of the original object or the memories and emotions that the object embodies? Similar to the layers of yarn it takes to conceal each object, layers of trust are built and relationships are formed; one between myself and the donor, one between myself and the object, and one between the donor and the art community.